GSD Thesis: Inside-Out: An Investigation of the Assembly Space as an Equitable Mediator in the Wake of Climate Change Disruption, Harvard Graduate School of Design, Spring 2020

Primary Adviser Ashley Schafer / Secondary Advisor Rahul Mehrotra

My thesis is ambitious in scope as the very problem of climate change is vast and seemingly impenetrable. It is simultaneously a love letter to Kahn, a respectful curiosity, and an attempt to solve a relatively new problem by affording a lens that has seldom been utilized. In as many things that I do not cover I, above all else, seek to find justice in an inequitable world brought forth by environmental irresponsibilities, and bring this to bear as a proving ground for what could and should be.

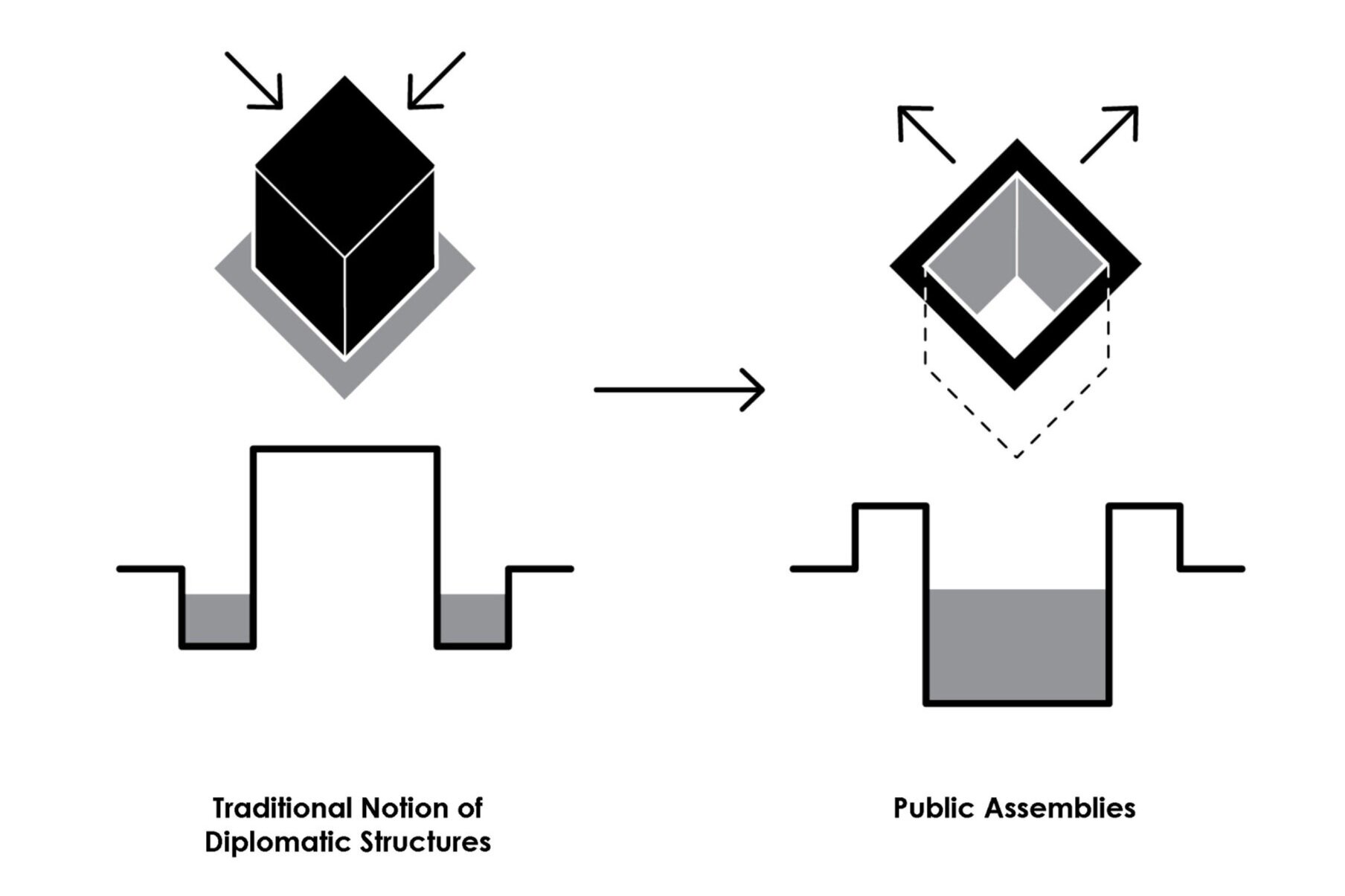

In this approach, I seek to explore the Assembly model (among others) as a viable implementor, educator and generator of adaptive climate-change strategies. Through inverting the perimeter wall model of western diplomatic architecture, introducing time as a medium of design, and questioning the antagonistic relationship of water to the built environment, I propose an approach where siloization gives way to international cooperation. These mechanisms can inform a less obscured form of diplomatic action that can be re-contextualized within a global framework of mitigative action.

This research was first organized into four main points of inquiry starting with the context, culture, site and finally design of this mediator situated in the heart of Bangladesh, in the very seat of democracy of Dhaka.

CONTEXT

From 10,000 feet up

“Bangladesh is set to suffer more from Climate Change by 2025 than any other country in the world”

My fascination started two semesters earlier in an attempt to fathom the effects of climate change to global populations and seeing the stark projections reveal themselves in the immediate future. For a place like Bangladesh, highlighted within the red box, with a minimal contribution to global warming and an average 4m elevation above sea level, they are set to suffer some of the worst effects than most other countries with a quadruple population boom by 2050 ➁. The environmental effects can and are being perceived with escalating flooding from cyclonic events and looming droughts.

Global Migration Pattern Study (multiple sources), Spring 2019

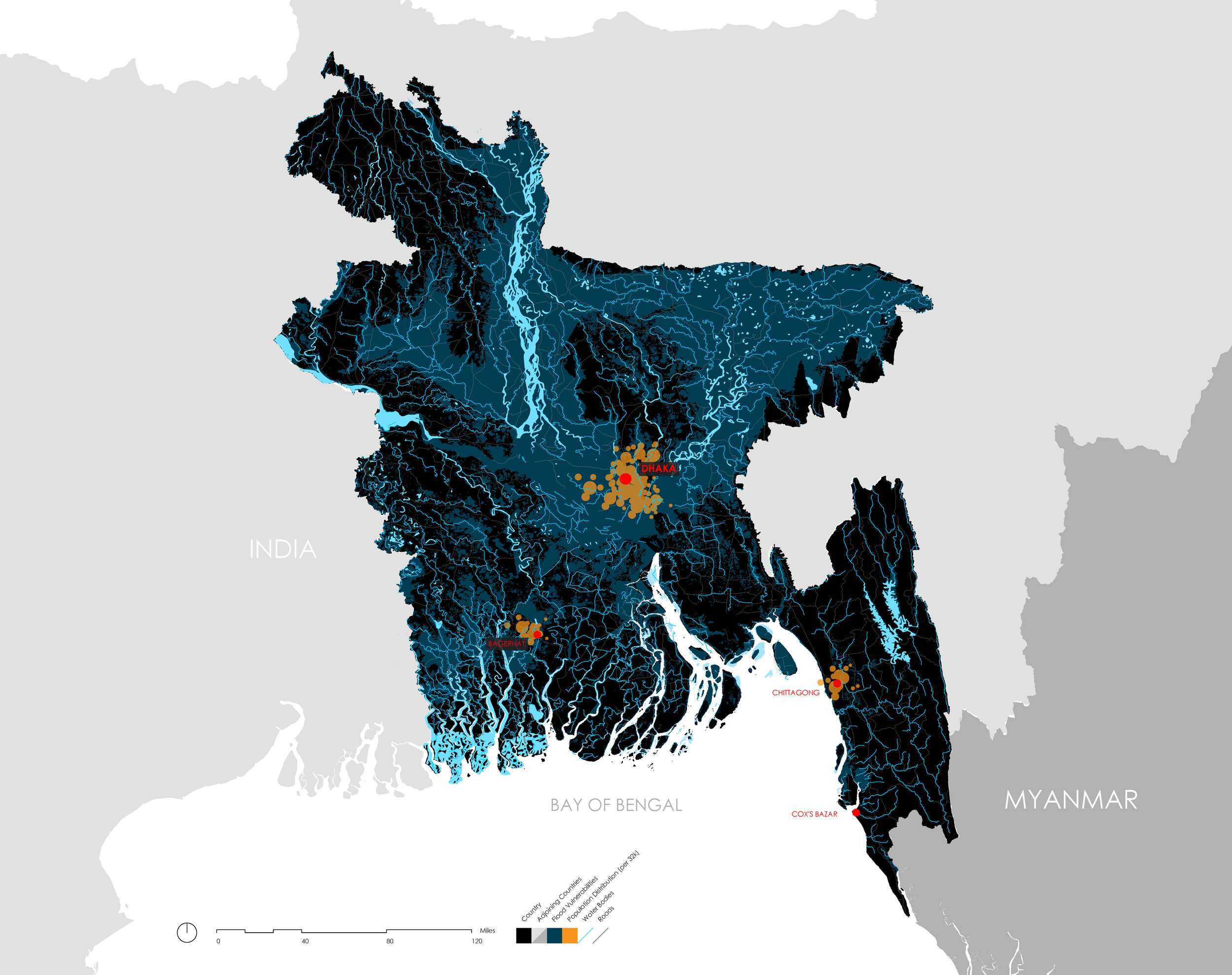

Map of Bangladesh with overlays of flooding vulnerabilities, population distribution, and connective infrastructure (multiple sources)

This is a country so intrinsically tied to the water as to reveal its beauty and reckoning: the Ganges and outlying rivers that flow from the Himalayas inundate as much as 70% of the country during the rainy season. Population booms in Chittagong and especially Dhaka will exponentially increase the country’s threshold for effective short-term responses from their biggest threat: flooding ➂.

In low-lying countries like Bangladesh drought, flooding, frequent cyclonic activity, and the escalating influx of people (often considered climate refugees’ ➃ ) toward larger cities like Dhaka, are becoming certain realities. Within the nation’s capital, new models of public assembly can serve as exemplars in rethinking the dialectic between colonial imperial approaches, or local reactionary maladaptive practices.

In revealing the country’s beauty, Yann Arthus-Bertrand’s mesmerizing satellite imagery of the Sundarbans ➄ illustrate the waterbodies as beautifully criss-crossing, fractal plates shifting into landfall, enmeshing itself not only into the topography, but into every cultural nuance of its populace.

In Dhaka, a city that is twice as dense than NYC in less than half the size ➁, public space becomes sacred and shrinking every year due to the demand for cheap living. For this reason, it’s important to allow space to be flexible and useful year-round.

These early notions of environmental, social and spatial data points introduced me to the country, but offered me little else in terms of its cultural nuances that are so integral to harnessing design solutions. I needed a more personal relationship with the country if I intended to pursue solutions from my desk in the studio.

CULTURE

From 10 feet away

In mid-January of 2020, I received funding to visit the country for two weeks to speak to practitioners, researchers and scientists on the topic of climate change impacts to the built environment, and the escalating issues facing the country. My short trip was relegated to Dhaka, where I hoped to delineate the site boundaries to test my architectural instigations.

There was no shortage of inspiration against the backdrop of a culturally rich culture that has evolved multiple times over to reveal unwavering beauty across the nation.

Mosques, Lalbagh Fort and Dhaka University in Old Dhaka

Bait Au Rouf Mosque (by Marina Tabassum 2017) in North Dhaka

National Martyr’s Memorial in Savar Union (North West of Dhaka)

National Parliament Building in Dhaka (Louis Kahn, 1971)

Among the many illuminating experiences, I was witness to the strong nationalistic pride evocative in the nation’s stark monuments, often times somber and imposing yet indicative of the country’s resilience through times of hardship.

I was most interested in the national parliament building campus, which served as a symbolic gesture toward a future of independence following the 1971 annexation from Pakistan, and a jumping off point to consider tackling a new challenge that hasn’t been fully addressed.

The national campus site could act as a catalyst to better understand possible opportunities that could be leveraged in light of impending challenges to the nation. Louis Kahn’s envisioning of a master plan for the country’s Democracy in its infancy, pictured in the center below, serve as fertile ground to safeguard and experiment against further challenges the country may face while bringing awareness to the its own internal resources and strengths.

City of Dhaka with areas of interest overlaid (multiple sources)

SITE

Learning from Kahn and the like

“The physical conditions of the region demand a positive design attitude towards the elements of the sun, wind, rain and floods”

In a country with limited support and dwindling resources, can a building seek to leverage a country’s soft power as cultural, political and foreign capital to a complex issue? Can a platform for engagement be established with the government to institutionalize sweeping change? Will establishing an educational framework help to craft a more resilient model in the wake of an uncertain future?

These were the questions I sought to explore. Upon my return to the States, I started with understanding Kahn’s machinations toward developing a symbol as both an outsider and design propagator. Following many years of internal strife and fluctuating economic capital, the master plan, within the region known as Sher-E-Bangla Nagar, only saw the realization of the parliament building, flanking hostels, and hospital to the North East of the campus. The assembly became a monolithic home for the government’s 371 parliamentary members since 1973. It is one of the largest legislative complexes in the world at 823,000 sq ft. In the end, Kahn called the assembly, “places of well-being, rest and where one gets advice about how to live forever.” ➅

The north end of the master plan attained the moniker of the Citadel of Institutions, however it was never constructed. Over 10 years worth of study, Kahn envisioned an intermingling of the arts and public infrastructure that mirrored the mission of the Assembly. He called it an “inspiration of how to live within the world.”

Yet for a building that was meant to serve the public, there are walls along the perimeter with numerous security points surrounded by barren and unused open fields. This has not become the point at which the public engages with their government. The constraint of security serves as a reminder of the distinction between the two.

Parliament building master plan overlays and their evolution from 1963 to 1973, redrawn ➆

“...the prevailing idea of the plan came from the realization that assembly is of a transient nature... these are places of well-being and places for rest and places where one gets advice about how to live forever. ”

However, the site North of the parliament building, in the red poche below, within the aforementioned Citadel of Institutions, is on a 32 ac area that has more in common with this original intent of inclusionary design. Currently this is the site for the Dhaka international Trade Fair in use for 1 month in the year.

Dhaka International Trade Fair (multiple sources)

From the beginning of January to the first week of February, and in the span of a few weeks, the fair is erected with over 700 stalls and pavilions, frequented by hundreds of thousands of people. For this one month, the full gambit of consumables are on display in the selling of local and international products. Lacking an infrastructure for this event to occur, the site serves as an abandoned field 11 months out of the year, with the echoes of the makeshift pathways peeking through the terrain.

I perceived this as an apt metaphor to the cyclical nature of flooding in the country, a potential to give back useable open space to the public and an opportunity to explore an unrealized vision for the site.

An early site model to situate the site in relation to the campus at large. An overlay of flooding vulnerabilities from multiple data sources illustrate a pervasive threat from the Buriganga River not only to the parliament building but the surrounding area as well.

Design

The Inverted Diplomatic Campus

“Embassies are symbolically charged buildings uniquely defined by domestic politics, foreign affairs and a complex set of representational requirements... Their history adds to our understanding of the present as new constraints define diplomatic architecture.”

With the site specified and Kahn’s master plans acting as the fulcrum, I sought to leverage the diplomatic construct to systematically reinforce strategies to safeguard against climate-related devastation. In an era of unprecedented catastrophe and uncertainty, we must consider a flexible diplomacy, one that is interconnected, global, yet decentralized.

Jane Loeffler said in the Architecture of Diplomacy that, “embassies are symbolically charged buildings that are constantly changing under new diplomatic constraints” ➇. However it is because of those constraints that their effectiveness becomes hindered. In answer to that limitation and in a time of uncertainty, this project considers a bottom-up approach to address long-term change from both a cultural and politically-charged intervention. I sought to enter this problem from 3 different archetypes:

01 embassyyssabme

Studies of 13 US Embassies on foreign soil, and their inverted counterparts, discovering a program that is vastly different than the original (see attributions for full list) ➇

The first exploration was the Embassy as strategy. In my research, there are no direct precedents that act as cultural institutions in partnership with government bodies addressing climate change action. However investigating embassies served as an appropriate introduction. Early on I sought to ask the question: Can a diplomatic archetype appropriate these strategies? Since “embassies are points of contact between peoples” it made sense to start the investigation there: how they served the public, what they provided to host countries, what they represent and how their evolution led to one of the most rigorously developed fortification structures in the world.

I studied 13 well-documented American embassies from 1950 to 2013 looking at access, circulation, and internal logic . Over time, what became clear was the imperative to limit and protect access above all else, a constraint borne from the programmatic requirements.

A later study looked at inverting these programs, if security wasn’t an issue. It was surprising to find that from many rigid structures there were also opportunities where plinths became moats, covered structures became open air courtyards, walls became ramps. This helped to illustrate that sensitive and elegant solutions can be sought without the use of barbed wire and bollards, and perhaps there was another way to choreograph security.

US Embassy in Dublin by John M Johansen (1957)

US Embassy in Oslo by Eero Saarinen (1955)

US Embassy in New Delhi by Edward Durrell Stone (1954)

“Embassies are points of contact between peoples...”

Opportunities began to emerge that resist the prototypical constraints of bureaucratic involvement. Once hampered by the ever-dominating constraint of a secure perimeter, one can see methods for finding a balance between an open-air assembly and a defensible perimeter.

Incorporating GSA security features into landform strategies (Source: GSA Standards)

02 ylbmessaassembly

The second archetype sought to dissect assemblies that promoted access while negotiating large groups of people. Certain assembly spaces, such as the National Parliament and UN building in NY occupy a coplanar relationship with that of the subject and person. These relationships, that of homogeneity and inclusion, help to elucidate an appropriate response to climate change action.

This reveals an opportunity for resource sharing and information gathering that can be fostered and allowed to prosper. The backbone of which needs to accommodate an assembly of diverse needs and functionality. The best example that I have found of this engagement in a political discourse within a controlled environment has been the Assembly of Nations within the UN building in New York. This helped to lend a great deal of inspiration toward the scale and directive of such an agenda.

UN Assembly of Nations research (multiple sources)

“The significance of the Capitol Complex is inextricably linked with the national and political movement of the Bengalis.

It is this correspondence between architectural form and cultural norms, often working at surreptitious levels that has not been fully investigated”

03 localityytilacol

“Akin to Kahn’s way of conceiving his ponderous architecture, the theme of stacking [in Chowdhury’s work] leads to the phenomenon of grounding, of building up an edifice as something bound to the earth, rising up rather than related to the ground mercurially.”

The third and final approach sought to explore the regional architecture in Bangladesh that emphasized the principles of the environment’s particular relationship with its context, and especially with water.

Kashef Chowdhury’s Friendship center, situated in its rural outskirts, leverages a “grounding” architecture, excavated partially due to the project’s economical constraints. Allowing the ground floor to flood brings a heightened awareness of the built form’s enduring and sympathetic relationship with water in the country. ➈

URBANA’s museum of Independence in Dhaka evokes the somber monumentality and hopeful outlook so evident in the country’s more contemporary of structures, that leverages the use of water as a focal point of the design. ➈

Using these 3 archetypes as guidance, the concept was marvelously simplistic yet extraordinarily complex: an inversion of traditional notions of diplomatic structures into public assembly spaces where a program would seek to be open and engaging to the public, ultimately helping to facilitate a dialog to occur with their government.

The Kahn master plans for the Citadel of Institutions envisioned an encompassing complementary scheme where a grand stadium was flanked by a series of markets and institutional keystones to advance the cultural strengths of the Bengali people. ➆

Can a reciprocal program strengthen and safeguard the diplomatic agenda? What does a diplomatic structure look like once stripped from its bureaucratic constraints?

An early section bubble diagram of the campus’s program, with an overlay of flooding projections

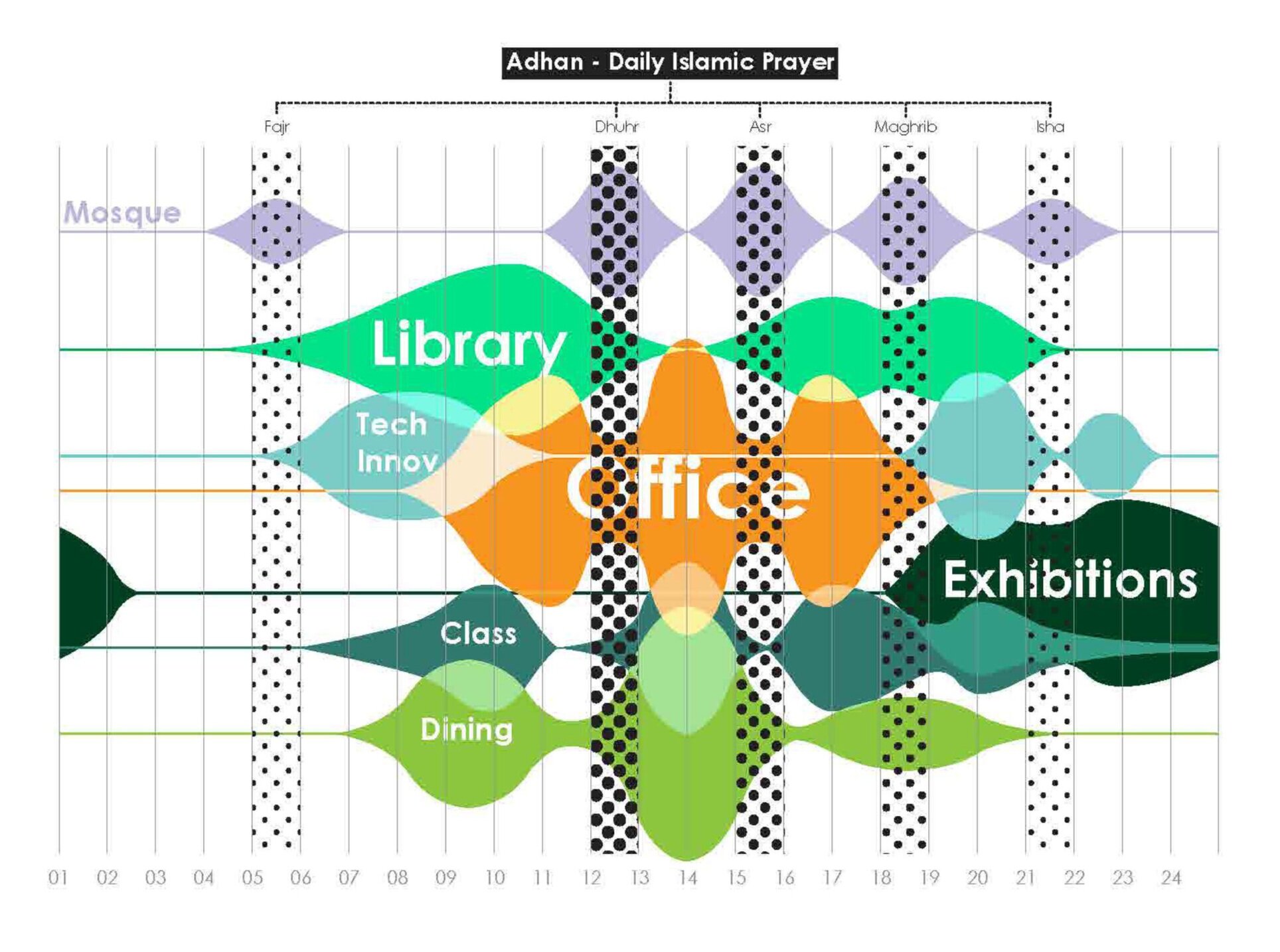

This program diagram considers the implications of Kahn’s Citadel of Institutions within the framework of time. The final design incorporates this programmatic scheme: The left half administers and implements while the right exhibits and experiments with the assembly being the conduit for this activity to occur. This mirrors Kahn’s original intent for the Citadel of institutions. Flooding projections illustrate a key constraint in the functionality of these programs, so time becomes an important consideration

Daily analysis of programs

Yearly analysis of country influencers (religious, environmental and events)

Early study models attempt to broker the country’s precarious relationship with water while forming the space required for a public assembly and the programs to support it

Spawning from speculative Kahn master plans, these forms were stretched and reconfigured across the landscape

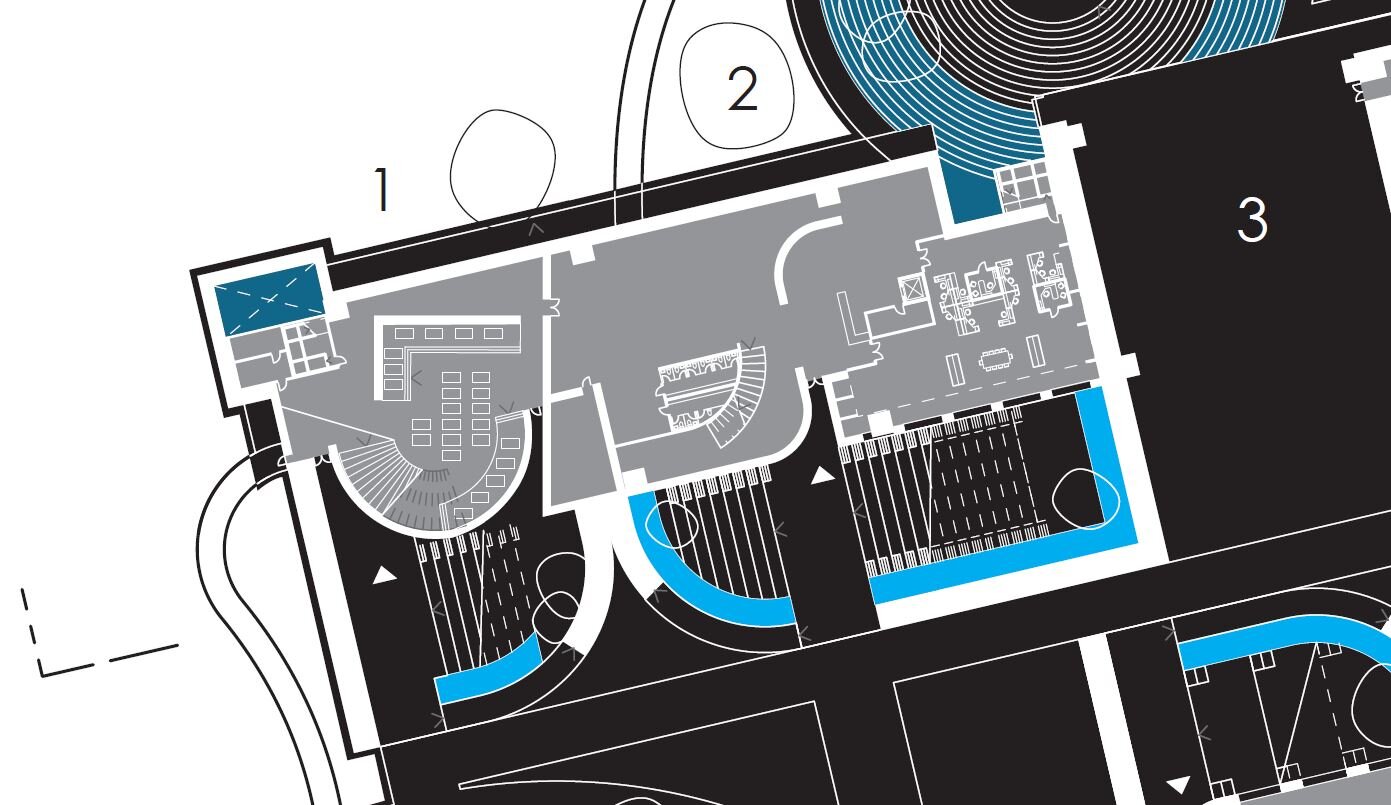

This site in question, situated north of the Parliament Building, abuts a major thorough way and international Conference center to the East, and national monument in Zia Park.

Kahn’s Citadel of Institutions forms the template to consider an overlaid plan of inverted reciprocal programs. This also helps to emphasize the axial relationship of the campus.

While the site is generally considered to be flat, there are low points to the east and west. Flooding projections anticipate complete inundation of the site within the next couple of years so these open forums have dual functionality.

Most of the tectonic expressions are also load bearing elements. The Primary structural components are a mixture of freestanding oversized poured-in-place concrete ribs to support the concrete stepped roof slab.

Circulation is controlled through the central spine with progressively thinner thresholds as one moves toward the center. This diagram shows access through different means of control in colored circulation.

Green is fully public, while orange and red are more controlled. While some access allows for a finer degree of control, a majority of the design is completely accessible, first from the central entrance to the north, and outdoor auditoriums to the Eastern and western-most part of the site acting as vertical datums (click on the animation for an enlarged version).

The programs are meant to be interconnected and flexible to serve a variety of events happening independently or in concert to handle an influx of people as needed. Areas in grey are indoor and black are outdoor and/or covered. There is a gradient of different use over the site, quantitative programs on the left half and complementary qualitative programs on the right.

With a minimal profile, the site is meant to be unobtrusive within the campus, a grounding architecture, quote “from the spirit and nature of the problem,” as Kahn himself said.

The retention ponds and assembly spaces along the periphery capture site runoff and over time water moves through the reservoirs and into the interior spaces over a period of storm surge, cooler interior spaces during warmer months.

Water flow and retention calibration throughout the site

Categorization of public assembly spaces located throughout the campus (click for enlarged picture)

The public assemblies are the heart of the project. Their distribution throughout the site affords the flexibility to engage in relevant discourse, with over 360,000 sq ft of diverse space.

There are 8 retention ponds for the 32 acre site. They are calibrated to address a worse case scenario that historically brought 333mm in one day (encompassing about 1.5 million cubic feet on the site). Flooding predictions need to retain at least 4.8 million cubic feet depending on the time of year (May to July are traditionally the wettest months of the year).

The current decentralized scheme can retain up to 12.8 million cubic feet, almost double worse case scenarios, however a properly calibrated site can retain up to a third more and still function without impeding the original design intent.

Exterior aerial during dry, rainy and yearly events. The “rooftop terrain” acts as the connective backbone for these interventions to occur, as the Dhaka International Trade Fair once did on the ground level, while making the site accessible and useable all year round. The project seeks to elicit moments of catalyzation for the country.

Longitudinal sectional perspective through the campus (click for animation). In this bent longitudinal section one can begin to see the push and pull of a grounded architecture in its context. Filligree brick screen walls allow light, air and water to pass through unabated while covered canopies help to temper the interior conditions. Ramped entrances allow unfettered access to the roof surface.

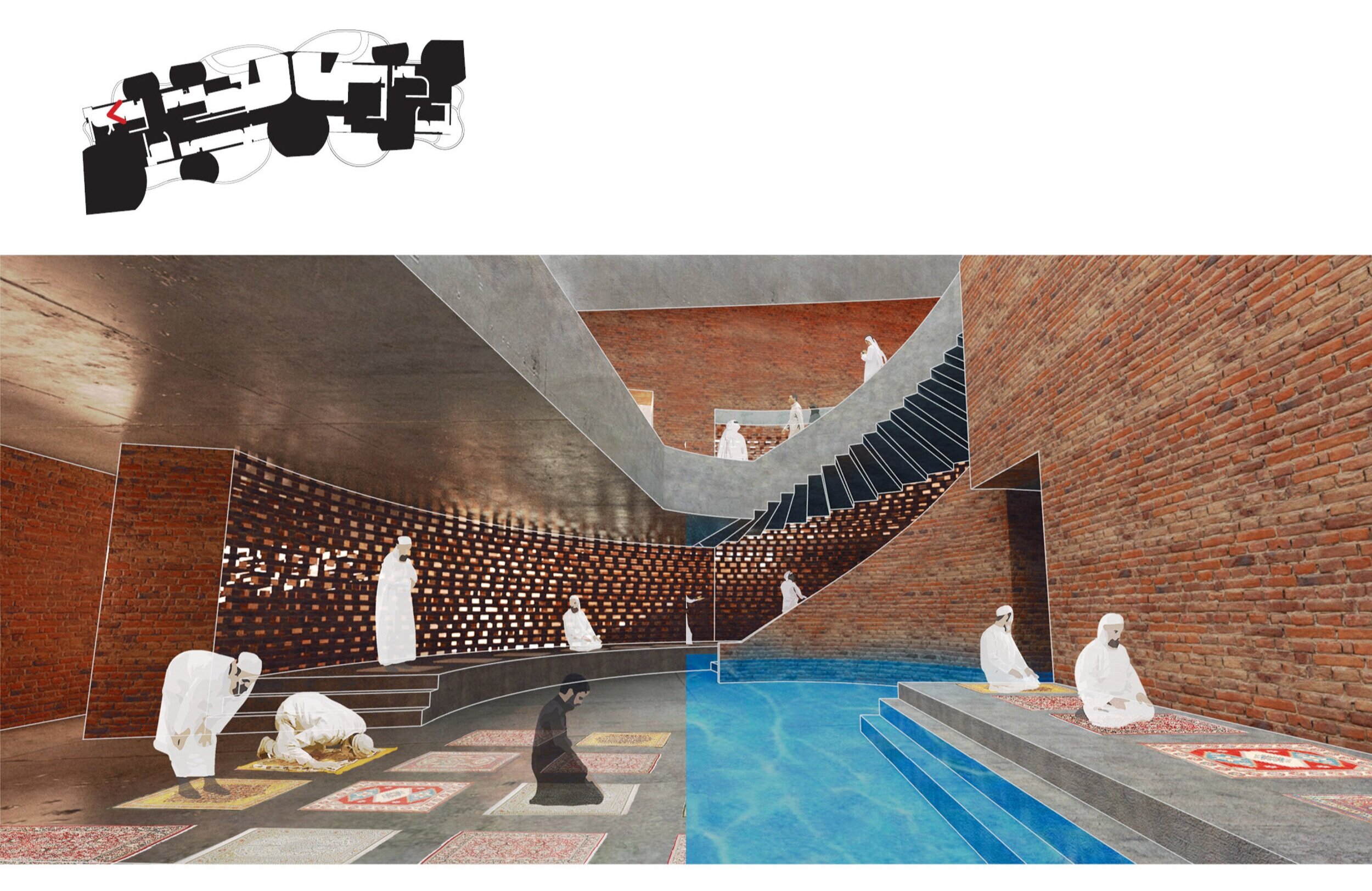

Mosque exterior. These internal moments are interconnected and flexible, manifesting spatial microclimates that service a larger vision for the country

Mosque interior, during dry and wet seasons. These become places of worship where light, air and water are integrated through filigree brick screen walls in filleted forms. The material evokes a monumentality simultaneously delicate while remaining sympathetic to local production practices.

Central outdoor auditorium. Concrete highlights the moments of water infiltration, reflecting light without heat on its polished surface, undulating as the water ebbs and flows. It is here in the central outdoor auditorium that a call to action can be spurred, in the shadow of Kahn’s monumentality to the south, similarly disassociated from its time.

Interior auditoriums, during dry and wet seasons. The stage for conferences of an international scale occur within the central core, repeating the long arcs and tectonic gestures of the exterior. This is a space for debate, amelioration, and rectification.

Exterior library and event space, during dry and wet seasons. The library is a place of welcome retreat from the daily drone of the city, so encapsulating that any moment of silence becomes sacred. It is also a symbol of hope for those travelling from afar in answer to the question of: what next?

Library and exhibition interior, during dry and wet seasons. These are places of learning where one can get guidance of how to elevate their home along the coast through the latest slump footing design techniques, on exhibit in the library foyer.

This project is a hybridization of civic, infrastructural and monumental strategies as a response to the incalculable problem of climate change. It serves as a new model of universality in arming a country with the regional knowledge and technology to address vulnerabilities with long-term adaptation strategies.

If an optimistic future can be built where a global dialogue of climate change action can occur, countries cannot solve these extraordinarily complex issues operating in a silo. As waters continue to rise in Bangladesh and around the world, a resilient architecture needs to respond accordingly. This model serves as a pilot program that considers leveraging internal growth and education as a catalyst for informed design interventions that are contextual. In time, this can serve to reinforce a new archetype that can be implemented in other vulnerable regions around the world.

attributions

❶ Climate Change statistics. October 2013, 30. “Global Economic Output Faces High Climate Change Risk.” Verisk Maplecroft, https://www.maplecroft.com/insights/analysis/global-economic-output-forecast-faces-high-or-extreme-climate-change-risks-by-2025/. ❷ Statistics on global population projections. Stern, N. H., and Great Britain, eds. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review. Cambridge, UK ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 2007; Hoornweg, Daniel, and Kevin Pope. Population Predictions for the World’s Largest Cities in the 21st Century. Environment and Urbanization 29, no. 1 (April 2017): 195–216; ❸ Environmental flooding data of Bangladesh. International Bank for Reconstruction and Development (IBRD), The World Bank. Flood Risk Management in Dhaka: A Case for Eco-Engineering Approaches and Institutional Reform. Disaster Management. (Bangladesh: GFDRR, World Bank, 2018). ❹ Foundation, E. J. (2019, October 10). from Environmental Justice Foundation website: https://ejfoundation.org/who-we-are ❺ Satellite image attribution. Arthus-Bertrand, Yann. Earth From Space. Abrams, 2013. Pg 165. ❻ From literature obtained and translated on-site of the Bangladesh Parliament Building. ❼ Redrawn Louis Kahn master plan studies of Sher-E-Banglanagar, National Capital in Dhaka, Bangladesh (1963-73) and quotations. Ronner, Heinz, and Sharad Jhaveri. Louis I. Kahn: Complete Work, 1935-1974. 2nd rev. and enl. Ed. Basel ; (Boston: Birkhäuser Verlag, 1987), 234-265. ❽ United States embassy photos and drawings for 3D models and analysis. Loeffler, Jane C. The Architecture of Diplomacy: Building America’s Embassies. Rev. 2. ed. (New York: Princeton Architectural, 2011); Ashley Schafer, et al, OfficeUS Agenda. (Zurich, Switzerland: Lars Muller Publishers and PRAXIS, Inc, 2014). Embassies shown: Harrison & Abramovitz, US Embassy in Havana, Cuba (1950) and Rio de Janeiro (1952); Skidmore Owings and Merrill, US Embassy in Frankfurt, Germany (1952); Edward Durrell Stone, US Embassy in New Delhi, India (1954); Eero Saarinen, US Embassy in Oslo (1955); Harry Weese, US Embassy in Ghana (1955); Walter Gropius / Ann Beha, US Embassy in Athens (1956); John M Johansen, US Embassy in Dublin (1957); Marcel Breuer, US Embassy in Hague (1957); Kallman McKinnell and Wood, US Embassy in Dhaka (1983); Arquitectonica, US Embassy in Lima (1992); OMA, Netherlands Embassy in Berlin (‘97-03); Kieran Timberlake, US Embassy in London (2013); Morphosis, US Embassy in Beirut (2017). ❾ Case study analysis for 3D models. Chowdhury, Kashef. The Friendship Centre: Gaibandha, Bangladesh. (Zurich: Park Books, 2016); Ruby , Andreas. Bengal Stream: The Vibrant Architecture Scene of Bangladesh. Christoph Merian, 2017. Pgs 171-175. ❿ Supplementary analysis and background information. Selim, Samiya A., et al. The Environmental Sustainable Development Goals in Bangladesh. Routledge Focus on Environment and Sustainability. (London ; New York, NY: Routledge, 2019).

Post-processing visualization support from Melanie Silver-Gallegos, Benoit Miranda, and Joshua Kuhr.